An essay by José Miguel Álvarez Stefanoni.

Abstract

To discuss a common theme across authors as diametrically different and unique in their styles as James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, and Franz Kafka proves to be a demanding task. Nonetheless, that is not to say that such a common theme cannot exist. Indeed, in this paper, I argue that one can find the concept of exile in much of the authors’ work. Joyce’s collection of short stories Dubliners, and in particular its concluding The Dead serves the theme well, as does Joyce’s only extant play Exiles. These works feature self-exiled characters who mirror the author’s own life in several ways, as well as personify and criticize Dublin’s complicated social situation and expulsion or separation from the rest of the civilized world. Beckett’s approach to this theme is quite different from Joyce’s; namely a welcoming embrace of exile, homelessness, and in-betweenness as existential and eternal. Just like Joyce, Beckett imprints these attributes in different ways onto the characters of his later work, such as Murphy, Molloy, First Love, and The Expelled. In Kafka, we encounter protagonists who are absolutely extraneous to mysterious and complex mechanisms, mirroring the author’s contradictory willingness to live a life of exile, away from the world and in a deep basement, where he is chained to his desk only to write and write. Kafka’s famous stories such as Das Urteil, Die Verwandlung, and Der Jäger Gracchus are all excellent illustrations. In spite of the three authors approaching exile from different angles, they all seem to agree on its central place in their work and their lives. For the purpose of concise analysis, in what follows I present an exploration of exile in Joyce’s intimate The Dead and Exiles, Beckett’s absurd The Expelled, and Kafka’s mysterious Das Urteil.

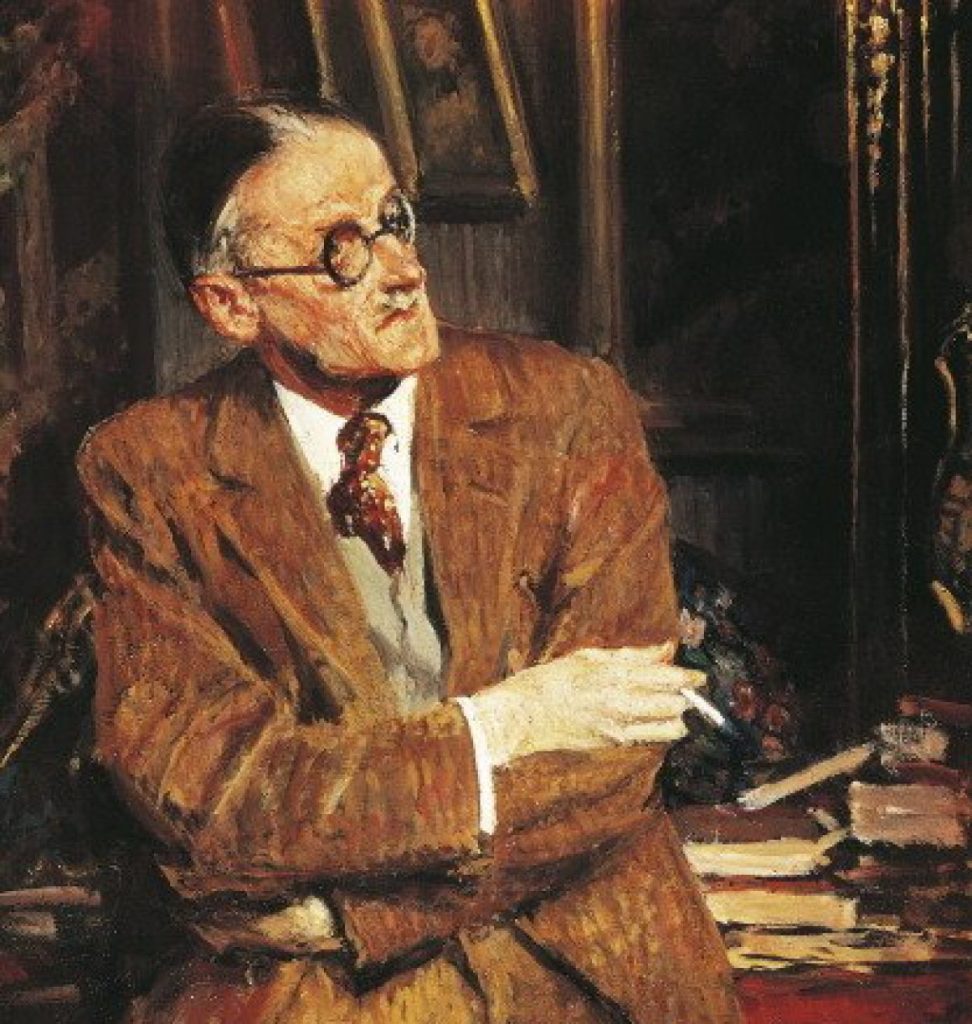

Let us begin our journey with James Joyce. The author’s life was in itself a self-imposed exile from his native Dublin, and so it shall serve as a good starting point as we explore this theme. In 1907 and living in Rome, Joyce wrote The Dead, which would become the last short story in his collection named Dubliners. One could claim that the entirety of the collection is in a way Joyce’s way to protest against Ireland’s paralysis and stagnation as a nation. However, The Dead particularly builds on this theme and showcases directly what the author thought about exile and the necessary, yet often painful separation of the protagonist from the dynamics of Irish social life.

The story mainly develops around a character named Gabriel Conroy and his awkward interactions with Irish society. All things considered, he’s a misfit in every scenario depicted in the story and feels nervous and somewhat paranoid about this. A clear instance of this presents itself when Gabriel is addressed by Miss Ivors, who despite simply trying to tease him by mockingly calling him a national traitor who doesn’t know his own land, manages to make Gabriel feel quite upset and insulted:

Gabriel glanced right and left nervously and tried to keep his good humour under the ordeal which was making a blush invade his forehead. … —And haven’t you your own land to visit, continued Miss Ivors, that you know nothing of, your own people, and your own country?… —O, to tell you the truth, retorted Gabriel suddenly, I’m sick of my own country, sick of it![1]

At the same time, we find that Miss Ivors is friends with Gabriel’s wife Gretta, who has an interest in exploring the Irish country by visiting her native Galway. To this, Gabriel reacts by showing no interest whatsoever in making such aspirations come true:

—There were no words, said Gabriel moodily, only she wanted me to go for a trip to the west of Ireland and I said I wouldn’t. … His wife clasped her hands excitedly and gave a little jump. … —O, do go, Gabriel, she cried. I’d love to see Galway again. … —You can go if you like, said Gabriel coldly.[2]

Here one can see a mirroring of Joyce’s attitude towards the desire of his own wife, Nora, to visit Ireland and strengthen her bonds with her native Galway. Drawing on more mirrors to Joyce’s own life, we find that Gabriel, just like Joyce, loathes the provinciality of Irish people and finds it thus impossible to exercise his profession there. Both Gabriel and Joyce were writers who longed to be distant from Ireland to be able to write. “Conroy, a provincial writer and teacher with Continental aspirations, parodies the greatness to which Joyce aspired”.[3] Furthermore, in a letter to Nora, Joyce wrote: “My mind rejects the whole present social order and Christianity – home, the recognised virtues, classes of life, and religious doctrines. How could I like the idea of home? My home was simply a middle-class affair ruined by spendthrift habits […].”[4] We can then observe just how strong Joyce’s position regarding his self-imposed exile was; he was not to be persuaded, and with that just like Gabriel he would continue to reject the pudding and take the celery.[5]

Exiles, Joyce’s only surviving play written in Trieste between 1914 and 1915, is perhaps an even clearer mirror of the author’s own life, and his reflections on the untraveled road if he had ever returned to Ireland with his family. We are faced with Richard Rowan, who is also a writer and undergoes a more complicated kind of exile: “Richard’s self-imposed banishment of nine years, though absolute, is also temporary, ending with his return to Ireland. […] At the figurative level, the exile recurs through the estrangements between the main characters. It is a spiritual separation that alienates one from the other.”[6] Inspired by Henrik Ibsen, Joyce sought to address the excess of freedom as a result of the character’s exile and the estrangements in the character’s personal relationships brought about by it. Rowan left Ireland in an attempt to escape his Ibsenian ghosts of conscience. Now that he has returned, however, he is set on leaving such ghosts aside by deciding not to interfere in his wife’s imminent infidelity. Joyce only returned to Ireland three times after leaving in 1904, and would never return after 1912. However, one could argue that the Ibsenian ghosts of his conscience were perhaps only strengthened by his self-imposed exile. After all, his relationship with his wife was at times strained because of his insistence upon separating himself from his homeland and his religion. On Joyce’s sentiments towards the Catholic Church, he wrote to Nora: “Six years ago I left the Catholic Church, hating it most fervently […] But at the same time, it was a sacrament which left in me a final sense of sorrow and degradation – sorrow because I saw in you an extraordinary, melancholy tenderness which had chosen that sacrament as a compromise, and degradation because I understood that in your eyes I was inferior to a convention of our present society.”[7]

Joyce therefore mirrored his own life of self-imposed exile and the complications that such a situation brought about by creating characters like Gabriel Conroy and Richard Rowan. Even when such exile is physically ended, as in Exiles, it does not quite disappear from the characters’ minds, as they shall forever be separated from their native land if they are to live; just like Joyce believed that only in exile could he recreate Dublin.

An interesting question arises on this point though: why would Joyce base his literary legacy on the place that he so wished to escape from? Why is every story in Dubliners, and even his 700-page Ulysses all about his native Dublin? A famous quote from Joyce reads: “For myself, I always write about Dublin because if I can get to the heart of Dublin I can get to the heart of all the cities of the world. In the particular is contained the universal.” If the heart of Dublin were representative of all the rest of the cities, what would be the point of his exile? Joyce’s characters in The Dead belong quite exclusively to a lower middle class with high aspirations, yet the author is sure to highlight Dublin’s almost glorified past and the crisis it currently undergoes. To understand the origin of Joyce’s exile, we must first understand the “personal and national sense of betrayal and outrage that had their origins in his own experience as a boy in Dublin […]”.[8] Dubliners itself is a hyper-realistic collection of narratives that bring together Joyce’s disillusionment and resentfulness towards his homeland’s social decline. As noted by his relatives, Joyce was in search of the truth of life, and his unshakable principles and beliefs would force him to take flight, offering a bird’s eye view of the Dublin he would spend his life sharing with the world.

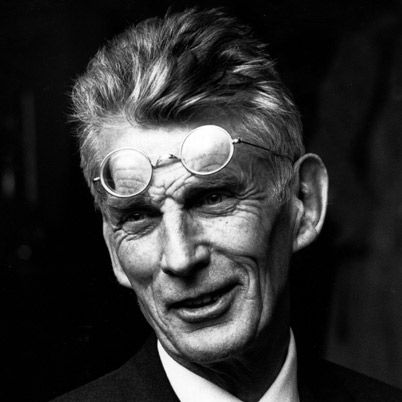

Let us now move on to a quite different approach to the theme of exile. Unlike Joyce, who had been forever marked by the difficult experiences of his youth, and understood the need for his self-imposed exile as a way to inspect his native land and reflect on his autobiography, Samuel Beckett had a much easier early life. He came from a well-functioning, well-positioned, encouraging family who sought to provide Beckett with the best education possible. Nonetheless, Beckett would then choose to embrace exile and walk difficult paths, which would lead him to become one of the most significant members of the absurdist movement.

Among his humorous aporia, there probably is no better representation of exile than The Expelled, written in 1946. Right at the beginning we find that the expelled man in question has been thrown out of his house by his family following the death of his father, an experience shared by a similar narrator in First Love. Interestingly, the contrary was true in Beckett’s life. His mother wanted him to stay in the house, but Beckett wanted out. As was previously mentioned, Beckett showcases an embrace of exile, and an attempt at universalizing this state by creating characters who do absolutely nothing but personify it:

So, for once, they had confined themselves to throwing me out and no more about it. I had time, before coming to rest in the gutter, to conclude this piece of reasoning. … Under these circumstances, nothing compelled me to get up immediately. I rested my elbow on the sidewalk, funny the things you remember, settled my ear in the cup of my hand and began to reflect on my situation, notwithstanding its familiarity.[9]

The agency of the expulsion is puzzling. We come to understand that the man has been thrown out of the house for unknown reasons by external agents. As is later noted in the story, we even take note that the man has experienced such expulsion for seemingly unjust reasons, as he claims:

I wasn’t afraid to look, for I knew they were not spying on me from behind the curtains, as they could have done if they had wished. … And yet I had done them no harm[10]

However, as the story progresses, we see in the man himself a desire to exit the places he goes into. After meeting the cabman and setting off in a search for new lodgings:

The addresses he had underlined, or rather marked with a cross, as common people do, proved fruitless one by one, and one by one he crossed them out with a diagonal stroke. … At each stop, he got down from his seat and helped me get down from mine. I rang at the door he directed me to, and sometimes I disappeared inside the house. It was a strange feeling, I remember, a house all about me again, after so long.[11]

The man then clearly is bound perpetually to exile not exclusively by others, but by himself too. It proves impossible for him to find appropriate lodgings, given the bizarre demands he has regarding the environment of his comfort. Only a bed is to be found inside of his room, something that has contributed to the perception of the man as fruitlessly looking for a womb-like environment to live in once more, after suffering the expulsion from the maternal womb. In his endless search for refuge, he exits one place and enters another, only to repeat the process over and over. “Two territories […] one territory to exit and one to enter into, and indeed the dichotomy between inside and outside is a prevalent topos in the story. Interiors and the comfort, safety and often warmth they provide abound, beginning with the double interior of the room in the house from which the protagonist was expelled.”[12] The story is a search for a comfortable, womb-like interior that contrasts the cold and desolate exterior. Even as the story comes to an end, the man expels himself from the stable of the cabman, only to wander aimlessly in his eternal exile:

I was cold, having forgotten to take the blanket, but not quite enough to go and get it. Through the window of the cab, I saw the window of the stable, more and more clearly. I got out of the cab. It was not so dark now in the stable, I could make out the manger, the rack, the harness hanging, what else, buckets and brushes. I went to the door but couldn’t open it. … So I was obliged to leave by the window. It wasn’t easy. But what is easy? I went out head first, my hands were flat on the ground of the yard while my legs were still thrashing to get clear of the frame.[13]

This remarkably ridiculous way of expelling oneself highlights the similarity to the expulsion of a baby from the womb during childbirth. Once out of the family home, the man finds nothing but homelessness and in-betweenness. The setting of the story itself could be anywhere among the perrons of Parisian houses, the funeral processions of Dublin, or the Lüneburg Heath in northern Germany. We are clearly somewhere, but we are also nowhere in particular. How can we come to understand what this means? What drives the expelled man’s unrest and exile?

Well, isn’t Beckett’s own life one of flight and refuge? His approach to exile is, as much of his work, an attempt at showcasing the decomposition of the human condition and human suffering. At the time of writing The Expelled, Beckett had had first-hand experience with war. He had found himself fleeing from the Gestapo as his first name erroneously placed a target on him as a member of the Jewish community, and his underground work with the resistance group ‘Gloria’ had forced him to lay low and hide.

Under these circumstances, one is able to catch a glimpse of just how Beckett thought of exile. It is not something that is self-imposed, nor imposed by others. Rather, it shall follow you wherever you go, pervasive and eternal. An “existential exile, a quest that will last from ‘cradle’ to ‘grave’”[14]. And this we perceive as the man in the story exits the cabman’s stable:

Dawn was just breaking. I did not know where I was. I made towards the rising sun, towards where I thought it should rise, the quicker to come into the light. I would have liked a sea horizon, or a desert one. When I am abroad in the morning, I go to meet the sun, and in the evening, when I am abroad, I follow it, till I am down among the dead.[15]

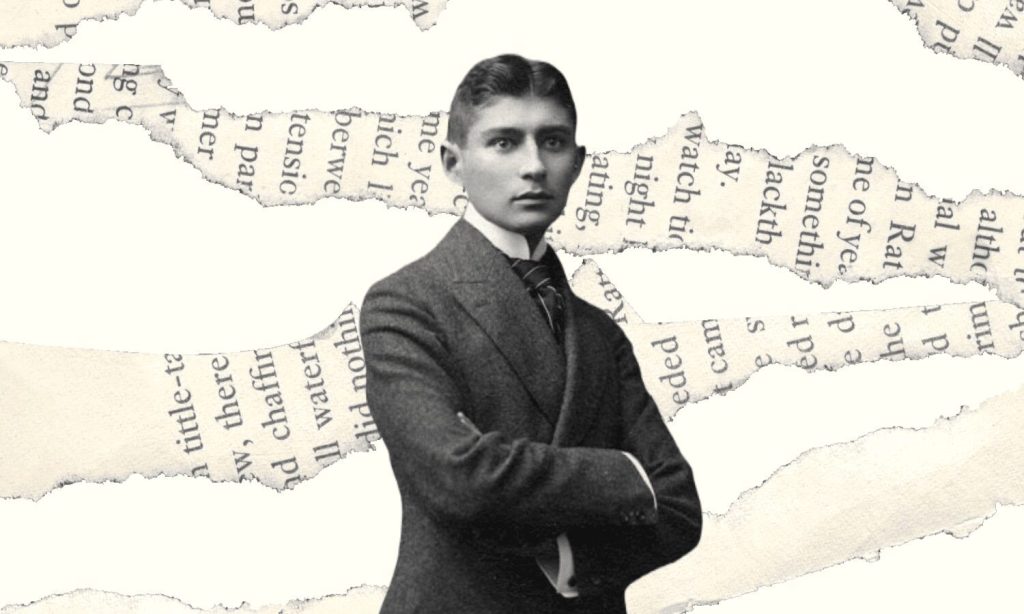

It is now time to venture into the bizarre landscapes of the mind of Franz Kafka. Das Urteil, written in 1912, was remarkably written in a single night as Kafka let his pen go free, losing control of what he wrote and thus imprinting onto the page what he felt and believed deep within. Just like we do with Joyce, we find much autobiographical material in this story. Nonetheless, I must insist that we dig deeper, since one shall find the strongest presence of exile among the pages of this story.

Georg Bendemann, a young merchant who is soon to marry, reflects upon his relationship with a close friend who has decided to move to Russia, away from his loved ones. This seems very strange to Georg, who cannot understand why his friend has made such decision:

He was thinking about his friend, who had actually run away to Russia some years before, being dissatisfied with his prospects at home. Now he was carrying on a business in St. Petersburg, which had flourished to begin with but had long been going downhill, as he always complained on his increasingly rare visits. … So he was wearing himself out to no purpose in a foreign country … and his skin was growing so yellow as to indicate some latent disease. … By his own account he had no regular connection with the colony of his fellow countrymen … so that he was resigning himself to becoming a permanent bachelor.[16]

From the beginning, by learning about Georg’s friend we are faced with an exile that appears to be self-imposed, much like Joyce’s. Such exile is incomprehensible to Georg, who now struggles to find a way to confess his engagement to his friend. As Georg recalls having explained to his fiancée, his friends’ determined exile would also prevent him from attending their wedding, which upsets her. Ultimately Georg takes the letter and gets up from his desk, heading into his father’s room. There we find a feeble and sickly old man who has chosen to live in a dark room, following the death of Georg’s mother. In the father we find yet another instance of self-imposed exile; this time from the outside world and human interaction:

It surprised Georg how dark his father’s room was even on this sunny morning. So it was overshadowed as much as that by the high wall on the other side of the narrow courtyard. His father was sitting by the window in a corner hung with various mementoes of Georg’s dead mother.[17]

As Georg tells his father of his intention to send the letter to his exiled friend, the father seems not to be very interested in the matter. As Georg covers up his father in bed, suddenly one of Kafka’s marvelous contradictions transforms his father from a feeble and worn-out old man into a dominating figure. The father goes from being skeptical about Georg’s friend to revealing that he has been sending letters to him quite often, claiming to have a privileged relationship with him. This destroys the exile of the father, and as his enormous figure towers high above the tiny Georg, we uncover the truth about exile in this story:

‘(B)ecause she lifted her skirts like this and this you made up to her, and in order to make free with her undisturbed you have disgraced your mother’s memory, betrayed your friend, and stuck your father into bed so that he can’t move’ … Georg shrank into a corner, as far away from his father as possible. … ‘What other comfort was left to a poor old widower? … what else was left to me, in my back room, plagued by a disloyal staff, old to the marrow of my bones? And my son strutting through the world, … Stay where you are, I don’t need you!’[18]

Paralyzed by his father’s unexpected reaction, we come to realize that it is Georg who shall suffer absolute exile; far away from his family, his friendships, and his marriage. It has all been taken away by his father who has always owned and dominated everything, and now the final sentence is made:

An innocent child, yes, that you were, truly, but still more truly have you been a devilish human being! —And therefore take note: I sentence you now to death by drowning![19]

Upon hearing this, Georg feels compelled to exit the house and jump from a bridge into the water underneath, as the noise from his fall gets lost among the traffic above. The exile that we experience in this story is perhaps the most powerful there can ever be for a writer. On this point, Martin Greenberg provides valuable insight: “The painful confusion in Kafka’s understanding of himself lies in his feeling that his solitary existence as a writer was forced on him by his father; and in his feeling at the same time that writing was his own deepest choice, so that his lonely bachelor’s life of exile from the world was something he was responsible for, an affirmation of his most authentic self”[20] It is Kafka’s exile from life. The Biblical commandment for him to die in his stories and be reborn.

Works cited

- Beckett, Samuel. I Can’t Go On, I’ll Go On. New York: Grove Press, 1976.

- Brown, Terence. Introduction. Dubliners, by James Joyce, Penguin Books, 1993, pp.viii-xlviv.

- Collinge-Germain, Linda. «Cultural In-Betweenness in ‘L’expulsé’/’The Expelled’ by Samuel Beckett.» Journal of the Short Story in English, no. 52, Spring 2009, 1 Dec. 2010, journals.openedition.org/jsse/959. Accessed 28 Apr. 2024.

- Greenberg, Martin. «The Literature of Truth: Kafka’s Judgment.» Salmagundi, vol. 1, no. 1, Fall 1965, pp. 4-22. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40546494.

- Joyce, James. Dubliners. New York: Penguin Books, 1993.

- Joyce, James. Extracts from the Letters. Letters II, August 29, 1904. http://www.ricorso.net/rx/az-data/authors/j/Joyce_JA/quots/quots5.htm

- Kafka, Franz. The Complete Stories. New York: Schocken Books, 1971.

- Mambrol, Nasrullah. «Analysis of James Joyce’s ‘Exiles’.» Literariness, literariness.org, 5 Jan. 2021, literariness.org/2021/01/05/analysis-of-james-joyces-exiles/.

- Munich, Adrienne Auslander. «Form and Subtext in Joyce’s ‘The Dead’.» Modern Philology, vol. 82, no. 2, Nov. 1984, pp. 173-184. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/437129.

[1] James Joyce. Dubliners. (New York: Penguin Books, 1993): 190.

[2] Joyce, Dubliners, 191.

[3] Adrienne A. Munich. Form and Subtext in Joyce’s «The Dead». (Modern Philology, 1984): 173.

[4] James Joyce to Nora. Extracts from the Letters. Letters II, August 29, 1904, p. 48.

[5] Joyce, Dubliners, 201.

[6] Nasrullah Mambrol. Analysis of James Joyce’s Exiles. Jan. 5, 2021.

[7] Joyce to Nora (continued). Letters II, August 29, 1904.

[8] Terence Brown. Dubliners, Introduction. (New York: Penguin Books, 1993): 13.

[9] Samuel Beckett. I can’t go on, I’ll go on. (New York: Grove Press, 1976): 174.

[10] Beckett, I can’t go on, I’ll go on, 176.

[11] Beckett, I can’t go on, I’ll go on, 182.

[12] Linda Collinge-Germain. Cultural In-Betweenness in The Expelled. (Journal of the Short Story in English 52, Spring 2009).

[13] Beckett, I can’t go on, I’ll go on, 184.

[14] Collinge-Germain, Cultural In-Betweenness in The Expelled.

[15] Beckett, I can’t go on, I’ll go on, 185.

[16] Franz Kafka. The Complete Stories. (New York: Schocken Books, 1971): 77.

[17] Kafka, The Complete Stories, 81.

[18] Kafka, The Complete Stories, 86.

[19] Kafka, The Complete Stories, 87.

[20] Martin Greenberg. The Literature of Truth: Kafka’s Judgment. (Salmagundi, Vol. 1, No. 1, 1965): 19.